Why Algae Won't Fix Beef's Climate Problem

Five Questions with Matthew Hayek and Jan Dutkiewicz on what you missed if you read those stories about feeding methane-reducing seaweed to cows.

My morning routine usually involves coffee and Twitter. I sip and flip, tweeting any coverage of food and farming that catches my eye. Usually I ignore the headline and pull out a specific quote but earlier this month, I tweeted this article about a new study looking at feeding cows seaweed to reduce their methane emissions:

Jan Dutkiewicz and Jonathan Foley (among others) were quick to respond, pointing out why this headline was misleading. The problem, at least one of them, is that the seaweed can only be fed to cows once they enter feedlots. The problem is that’s past the point in their lifecycle when they belch out the most methane.

Dutkiewicz and Matthew Hayek were already working on a response to the media coverage of this study, summing up what the coverage missed. In Wired, they argued:

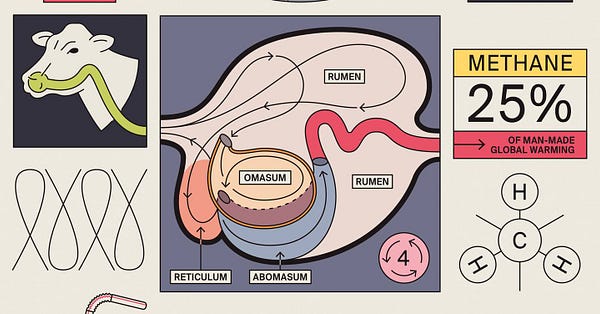

But on feedlots, cattle already belch less methane—only 11 percent of their lifetime output. That’s because most of their methane comes from their gut microbes breaking down the indigestible grass, leaves, and roughage they eat on the pastures beforehand, and not from feedlot corn and soy. This means that even if algae diets on feedlots worked perfectly, it wouldn’t help with the 89 percent of cows’ belches that occur earlier in their lives.

In other words, even though much of the media coverage touted the finding that seaweed additives could reduce methane by more than 80 percent, the actual number would be much, much lower, more like only 8.8 percent, according to Hayek’s and Dutkiewicz’s calculations.

I had more questions, so I asked Hayek and Dutkiewicz if they would answer five of my questions for my newsletter:

Five Questions with Matthew Hayek and Jan Dutkiewicz

edited for length and clarity

Splitter: Your piece in Wired was a reaction to the media coverage of these seaweed feed additives. If you could wave a magic wand, how would you want the media to cover this research?

Dutkiewicz: I mean, I would want to cover it the way that we covered it because, in a sense, what we were writing was a corrective to coverage that was completely uncritical of the research.

We took neither a contrarian nor a particularly deep dive into this issue. We simply took the facts as they were presented by the researchers, which is how they were presented by the media, and we just attempted to contextualize them with the basic questions one would ask: Can this scale? What are the problems with scale? Is this actually the reduction as claimed? Or are there perhaps basic logistical issues or animal lifecycle issues that would affect how these productions played out? So we asked basic questions that I think any journalist covering this fairly would have asked or should have asked if they were doing their due diligence.

Hayek: There also wasn’t really a discussion of the minimum reduction in methane that the researchers got in addition to the maximum. So, the maximum that they got was an 80 percent methane reduction but that was in the diet that already had the most concentrated feed, which is the diet that already produces the least amount of methane.

Splitter: I think I first heard about these additives in the massive report the World Resources Institute put out in 2018, where feed additives were cited as one solution among many, including eating a lot less beef. So in my head, I kind of already placed it in that context. But I’m wondering how you both view industry-side solutions. Is it possible to encourage them without greenwashing beef, especially given that the incentive for industry is that they want to be able to find a kind of marketing hook?

Hayek: I think it’s important to keep in perspective what this is. When we talk about marketing and product deployment, we often talk about B2B, business-to-business, or B2C, business-to-consumer. We’re getting ahead of ourselves talking about this as a business-to-consumer kind of product—that this is going to be something that makes you feel guilt-free about your burgers. It’s not. This is something that is in a very prototypical research and development stage, whether it’s a startup producing the red seaweed for another business or a university lab producing public research for a business solution.

If we do, say, have a carbon tax in place, it could help farmers keep their emissions a little bit under or, for an entire feedlot, dramatically under, but it’s not going to do that for Tyson’s or Cargill, or McDonalds or Burger King, or anyone else in the business of selling a lot of meat to consumers.

Dutkiewicz: I agree with everything Matthew said, and I would also just double down on my initial point—that I think here is where the due diligence really needs to be done by the media. By publishing stories like these uncritically, the media is de facto doing the greenwashing for the industry by telling consumers or by suggesting to consumers, that this is possible, it’s scalable, or it’s perhaps possible in the near future, and that therefore this sort of low-impact, ethically more acceptable, more climate-palatable, more guilt-free, however you want to put it—that this beef is around the corner. The consumer may then perhaps say, oh well then there’s no problem with beef or beef can be salvaged and saved after all, and I think that the media, in covering this uncritically, is doing a vast public information and public and planetary health disservice.

Hayek: I want to build off that a little bit. Climate media right now is covering meat the way they would have covered fossil fuels 25 years ago — look at all of this great stuff industry is doing. All you have to do is map animal agriculture onto fossil fuels and ask yourself, am I getting information from critical climate voices on this issue? Take Henry Fountain’s article for the New York Times on all of the things the meat industry is doing. Now, I love Henry Fountain’s coverage overall, but he totally dropped the ball on that one.

This coverage of meat would not hold up to the standards of scrutiny that the media currently has for fossil fuel companies. Take improvements in efficiency in coal and natural gas—we are burning at least 10, if not 25 percent more efficiently today—and while those efficiency gains are critical to meeting climate goals, they’re insufficient on their own for reaching a renewable energy future.

You can draw parallels between how the media is helping the meat industry greenwash their product and the types of uncritical boosterism that might have happened 25 years ago, with the coverage back then of technological efficiency improvements.

Splitter: In places like California and New Zealand, governmental bodies have set methane reduction goals and, in both places, lawmakers and regulators are working together with industry. Are there countries or states, or even a policy model for working with industry but also holding it accountable at the same time?

Hayek: John Lovvorn at Yale writes a lot about making animal agriculture internalize its externalities, and that’s essentially what we’re not doing right now. We’re subsidizing the grazing on public land. We’re subsidizing the corn production or, at the very least, giving them premium-free insurance, which is a subsidy in itself. We’re constantly giving pollution discharge waivers and discharge permits to concentrated animal feeding operations to exceed levels of pollution that other industries and cities would not be permitted to discharge. And now they’re asking for further subsidies for seaweed additives and for anaerobic digesters. So if you want to give them some subsidies, you also have to start—not even penalizing—but just asking them to pay their fair share. So I can’t think of one specific model for that, but I don’t think piling more subsidies on top of subsidies for a very polluting industry is the way to go.

Dutkiewicz: I would agree and, even more broadly, the animal-sourced food industry is under-regulated. There’s a paper that just came out by Nicholas Treich and other co-authors in France that suggest that given that the industry contributes to the risk of zoonotic diseases, there’s an economic case for a Pigouvian tax that would make them internalize the cost of that contribution to risk.

There also could be more binding animal welfare regulations at the federal level, ones with some teeth and enforcement—currently there are none—if practices like artificial insemination didn't have sexual abuse and bestiality exemptions in many state laws, for example. I think the question is less about policy or about funding research to mitigate climate harms, because I’m broadly in favor of mass federal investment in all kinds of applied and blue sky research into research for any kind of climate technology and climate mitigation, but the flip side of that is treating this industry fairly—forcing it to address all of these externalities and regulating it far more judiciously.

Matthew: And I think these zoonotic disease and environmental questions—they aren’t separate questions because we know that two of the biggest factors for zoonotic disease emergence are intensive animal confinement and deforestation, and both of them are not only linked to meat production but also, the more free range and extensive you make your meat production, the more of a carbon opportunity cost and deforestation pressure you incur. And on the other hand, with more intensification, the greater the risk of an outbreak in that particular place of production. So it’s either clear the forest or pack the animals in—unless you reduce consumption of animal protein.

Splitter: I also wanted to ask about the challenge of growing that much algae. I’ve heard from some academics who study algae and also people in the algae industry that we should be growing tons of algae because it’s this super sustainable food. So I’m just wondering what the problem is with growing a lot of algae to make feed additives. Is it just a problem of scale? That we could grow enough algae in aquaculture facilities for people to snack on, let’s say, but growing enough to feed the entire global cattle population would be too much? Or is it something about this particular type of seaweed that would be difficult to scale?

Hayek: It’s a tropical seaweed, and that’s important to keep in mind, because you can only produce it in tropical regions. Most of the concentrated production is happening in places like Europe and in the United States, places that are not tropical. So you either need to get a massive import-export business running or a massive shipping operation from Hawaii or Florida or probably even further south than Baja, or find ways to produce it indoors in controlled environments, but we know that the heating costs associated with creating tropical temperatures in winter months incurs a massive greenhouse gas footprint.

This is not like how Welsh farmers have been feeding kelp to their cows for years to improve their lactation rate. That’s great, but that doesn’t mitigate methane emissions by 60 to 80 percent. That just boosts productivity and efficiency by a little bit. This isn’t growing seaweed in the Hudson Bay or getting an aquaculture operation up and running in Iowa. We’re talking about a massive shipping operation from tropical regions.

Dutkiewicz: There’s just a huge question mark about whether or not this is economically viable. You have to set up entirely new logistical chains in order to make to make this work, and there’s no guarantee that farmers would necessarily buy it and it’s also unclear if this is can be incorporated into pastures. So you’re talking about basically creating a new value chain for an all new monocrop—making it viable, convincing farmers to buy it—all of that for potentially under 10 percent reduction in methane emissions, and that doesn’t address emissions from the manure, just belches.

It seems to me it would be far more efficient to grow algae directly for human food or for alternative protein applications. If we’re going to create a new monocrop—which itself is a question mark—we might as well get more bang for our buck. I think that probably lies in food for consumers rather than as an emissions mitigation strategy in the cattle value chain.

Splitter: I noticed in a press release for an earlier study from 2019, one of the authors raised a number of questions about whether these additives would be feasible, but the press release for a more recent UC Davis study, for example, didn’t include those questions. Is that a problem with the paper? With the press release?

Hayek: I think the UC Davis study was a good study. I have a lot of respect for what they were able to accomplish. Remember that most science is not silver bullet miracles or breakthrough science. It builds on the steps of previous studies. One of the experts that we cited was Alexander Hristov from Penn State, [co-author of the 2019 study looking at feeding seaweed additives to dairy cows to reduce methane emissions], an animal scientist who is concerned with greenhouse gas emissions. He’s close colleagues with multiple colleagues of mine, as is Ermias Kebreab [at UC Davis].

Hristov brought up the issue of potential adaptation and acculturation to the microbes [the question of whether cattle rumens would adapt and start belching out more methane again], and then Breanna Roque and Kebreab did a longer term field study with multiple proportions of forages to concentrate the diet and see whether that adaptation would occur. And the answer—the most novel part of that study—is that the adaptation did not occur, that these additives were effective at mitigating methane even as the cattle were eating more concentrated seaweed. That is a substantial research finding. So I don’t necessarily see this as a problem with the science itself. I think the reviewers of the Hristov study were asking the right questions, probably pressing him on the issue of adaptation, and then Kebreab and Roque did a great job building off of that information.

But, of course, it’s not just the dynamics of the science journal, right? When you do a press release for a study, the authors or primary author of that study writes the press release in conjunction with the communications officer at that university. So to the extent that there was language in The Guardian about this being some sort of breakthrough that will help our burgers be more sustainable, that was also the product of Kebreab’s lab, research environment and support group.

So it’s not the case that the journal wasn’t doing its work. It absolutely did. But again, this is about media uncritically mirroring the response of these industry-aligned research labs. We know that the UC Davis programs get funding, as you covered, from the meat and dairy industries, and there needs to be questions asked in the exact same way that if a fossil fuel research lab published studies into how to make natural gas more efficient if they were getting funding from the natural gas industry. We’d be asking further questions about it and we wouldn’t even have to say this research is wrong to ask those questions.

Major gains have been accomplished through combustion and turbine technologies to make gas and coal power plants more efficient in a way that we would be worse off if we didn’t have the right now. That being said, those breakthroughs are not a silver bullet for our climate system or for our energy system. In the same way, these seaweed additives are not a breakthrough for our meat and food production system.

Dutkiewicz: One last thing and, please don’t take this as an ideological position, but I think that all of these studies need to be tempered by what we already know. There are solutions now to our various climate crises that are implementable. We need to think much more about the solutions that are available now rather than grasping at silver bullet solutions, especially, as in this case, where the silver bullet solution isn’t even that promising.

There’s extensive research on this, look at the EAT Lancet Commission. We know that one of the easiest emission reduction strategies in food consumption is simply reducing meat consumption and, especially, reducing the consumption of beef. That’s out there, that’s de facto, more or less, scientific consensus, and it’s a solution available to us now. So I feel like any coverage that is talking holistically about GHG reduction in the context of livestock should also be mentioning what we already know.

Any story that is talking about hamburgers as somehow sustainable after all, should at the very least be mentioning that this is prototypical research. This is valid science but it’s prototype research that’s happening in labs, and we know we’ve got this existing solution, which is going more plant-based. This solution has been published in peer-reviewed journals and has been talked about by numerous NGOs, everyone from the World Wildlife Fund to the Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins. And so that should be getting far more press and should be getting covered in these same stories. If you’re talking about GHG reduction from animal-sourced foods, you need to also be talking about reducing animal-sourced food consumption.

Hayek: Fifteen years ago we were talking about coal with carbon capture, and there was really amazing and promising research into carbon capture and sequestration. That research was critical, but it was never a silver bullet. Media should cover that this technology is being developed and it’s on the horizon, but also cover what we needed to be doing yesterday too.

More: Want Carbon-Neutral Cows? Algae Isn’t the Answer

Also this week: I was on the What The Farm podcast: