The Lasting Impact of the GMO Debate

I was once excited to leave the GMO controversy behind. Lately I feel like I'm back where I started again.

I got into writing about food systems with the GMO debate. In 2015, the controversy was heating up and I was ready to argue. But at some point it started to feel like the conversation never really moved forward. Boosters hyped up the promise of GMOs. Opponents called them poison. Rinse and repeat. I started to feel stuck in a loop.

Once Congress passed its bioengineered labeling law in the summer of 2016, public interest in the controversy started to wane. By 2018, I was more than happy to cover something new: meaty-tasting plant-based burgers and chicken nuggets grown from cells. The food science was fascinating and the benefits seemed clear. Yet three years later, conversations and coverage around food and climate issues can feel just as fruitless and circular as arguing about GMOs. If the GMO debate had a lasting impact, it wasn’t a good one.

Our enduring obsession with all things “natural”

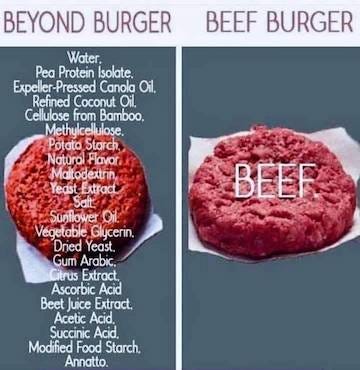

Once the alt protein industry started to get widespread press attention and tout some sales growth, the animal agriculture industry amped up its defense of conventional meat and dairy. The industry is a lot more than cattle ranchers and livestock farmers. Particularly on social media, the loudest voices are often “agvocate” influencers and the academics and scientists who work with the sector. One of the most common arguments is that beef is better because it’s more “natural.”

The same people who defended GMOs in the form of corn and soy for animal feed were now taking a page from their longtime organic opponents to critique plant-based meat. Plant-based burgers are fake, made in a lab, processed. “Real” meat is the more “natural” choice.

These same arguments come from the anti-GMO side too. In 2012, Michele Simon was a proponent of California’s GMO labeling law, Prop 37. She went on to found the Plant Based Foods Association, an organization she left in 2020. These days, Simon is calling on the USDA to reject the label “cultivated” for cell-cultured meat because it might confuse consumers into thinking these foods are “natural.” She prefers the term “biotech meat,” drawing a through-line from her opposition to GMOs to today.

Despite how heated these arguments get on social media, it’s not clear that consumers actually care about any of these labels when they’re shopping (how they answer a survey question like “do you want to buy foods made with GMOs” is an entirely different matter). The bioengineered label now appears on food, but it doesn’t appear to have made much impact on sales. Yet many plant-based brands chase the “natural” halo, marketing their products as “non-GMO” and the especially meaningless “clean,” likely because a marketing company told them it matters. While “natural” has its appeal, some consumers clearly will buy tech-y, future food, whether it’s for perceived health benefits, actual environmental benefits or just because they want to try it.

Isha Datar made this excellent observation:

I know there is this strong sentiment against "lab grown" - but the largest group of cell ag fans in the world (~60k people) are in a subreddit called r/Wheresthebeef, where it is explicitly called lab grown. Why are we leaving our first fans behind, the folks who are excited for the tech for exactly what it is?

Impossible meat, made in part with genetic engineering, is still a leader in the sector. So even though this argument of processed versus natural continues to take up space, it’s the least important aspect of alt proteins, just as it was with GMOs.

All we got was this lousy corn

There are also dangers in too much boosterism. One thing the GMO debate demonstrated is the problem of over-promising a technology’s benefits without ever talking honestly about its challenges.

Much like with GMOs (and all sorts of other hyped up agritech and food tech, like nitrogen-fixing microbes and anaerobic digesters), the science behind alt proteins is full of promise. At its most basic level, growing a nugget from some cells rather than slaughtering a chicken is a win for animals. And for climate emissions, no matter the processing or engineering that goes into them, alt proteins are undoubtedly, unquestionably lower in greenhouse gas emissions than beef and dairy. According to the research, funding these foods could help scale up production. The promise is great and absolutely real. But we shouldn’t just talk about the promise. The history of GMO boosterism demonstrates why.

I’ve lost count of how many times boosters have overpromised and underdelivered on GMOs. Take the allergen-free peanut, still trotted out as an example of what GMOs could do even though it’s still not on the market and probably never will be, for reasons I described in 2016. The more common example: we can’t feed the world without GMOs. More recently: we need GMOs to protect us from the climate crisis.

Again, the promise is there. GMOs are included in a number of climate solutions plans (like the World Resource Institute’s) because GMOs are high-yielding, more crops with fewer inputs. These higher yields can help farms reduce emissions, but other changes have to be made too, like limiting agricultural land expansion. On their own, higher yields aren’t enough to “solve the climate crisis.” Most GMO crops grown in the US are corn and soy used to feed methane-emitting livestock. We can’t just increase yields on feed crops. We also have to tackle the land use and the methane.

It’s the regulations, stupid

For years, GMO boosters have argued that the tech could deliver on all of its promises and more if it weren’t for the legal hurdles. And there’s some truth there. The regulatory system for GM food approval in the US and in other countries is slow and contradictory. Yet with CRISPR and gene-editing technology, companies are now able to get crops to market with fewer regulatory hurdles. But what do we now have to show for it? Despite a steady stream of glowing coverage on the new GMOs, we mostly have some non-browning french fries. And traditional GMOs are still mostly soy and corn.

Find nuance beyond the most obvious boosters

Push past the boosters and you will find people willing to discuss the challenges facing tech solutions. Isha Datar and Kate Krueger (who also used to work at New Harvest) have always been upfront about the hurdles for the cultivated meat industry, including the challenges to finding a replacement for fetal bovine serum, the feed originally used to grow cells.

Same with the GMO debate. Despite their longtime opposition to GMOs, the Center for Biological Diversity expressed support for Impossible and Beyond Meat burgers as a way to replace meat and protect biodiversity. At Scimoms, we’ve written about how GMOs are often a proxy for other systemic issues. My friend and fellow Scimom Kavin Senapathy has (on her own) written critically about biotech.

Though I’m quick to point out the benefits of higher yields and greater efficiency from factory farming, we have to talk about the downsides too. I’m troubled when boosters for industrial agriculture’s efficiency don’t talk about the industry’s many abuses, especially the unchecked power of corporations to pollute communities and expose their workers to covid so they can keep packing meat.

At the same time, I can’t give corporate marketing schemes that slap “regenerative” or perennial Kernza on a cereal box a free pass either. Just as with the tech solutions, there is some promise, even if it’s more for improved soil health than sequestering carbon. The problem isn’t the Kernza or the regenerative wheat but the media giving these more “natural” approaches a glowing endorsement without bringing up the challenges, like the fact that these foods would require significantly more land to scale up, which would ultimately increase emissions. This is no improvement on unchecked techno-optimism.

Policy action is necessary and still missing

Without enforcement and accountability, corporate solutions can only go so far. No matter what Certified B corps say in their marketing, the “just” corporation is a myth. Solutions like cultivated meat and Impossible burgers can help lower our greenhouse gas emissions but they can’t and won’t hold meat companies accountable for their actions, especially given that some are partnering with them.

We shouldn’t be satisfied with a handful of corporate-backed solutions, even the really good ones, without significant policy change that increases regulatory action and enforcement of the animal agriculture industry. But we have zero political leadership on that right now.

I feel conflicted when I think back how often I argued the scientific case for the safety of GMOs when the issue was never really ‘death by GMO’ but a slower, creeping devastation to our planet. Ultimately, even the best solutions run the risk of turning out like GMOs, full of promise that never quite delivers. Rinse and repeat.