New Study Finds 'Eat Less Meat' More Persuasive Than Veganism. So Where Does That Leave Animal Rights Activism?

Five Questions with the Reducetarian Foundation's Brian Kateman and Researcher Gregg Sparkman

A new study comparing the impact of the Reducetarian message with an appeal to eliminate meat found that “reduce” was far more effective. In fact, those who read the “reduce” op-ed ended up cutting their meat intake by seven to nine percent, and they did so for the entire five month duration of the study.

In this interview with lead author of the research, Gregg Sparkman, PhD, and President of the Reducetarian Foundation, Brian Kateman, we talk about the fascinating science of behavioral change, why incremental shifts work better for personal behavior than policy, why we still need animal rights activists, the problem with corporate-style positivity, and whether Jenny actually just needs therapy.

Five Questions with Brian Kateman and Gregg Sparkman

Edited for length and clarity.

Splitter: So, what surprised you most about the study?

Kateman: What surprised me most was that the intervention even worked. In the food tech space, there’s a strong belief that education doesn’t work in terms of changing people’s behaviors, especially around food. A lot of people don’t like factory farming. They’re against cruelty to animals. They believe in the value of eating fruits and vegetables in terms of their own health. But when it comes to their actual behavior, we don’t necessarily see a change.

That’s why we need plant based alternatives and cell-based or cultured meat, or at least so we’ve always heard. And when you look at USDA data, you do see that, for example, in 2020, meat consumption increased in comparison to 2019, so I think there is a lot of evidence to suggest that we need to make it easier for folks to cut back on animal products, but I personally was excited and even a little bit surprised that giving people information in the form of an op-ed was observed to be effective in getting people to eat less meat, particularly among that population of folks who were a bit younger and more educated and less wealthy. The jury’s still out on to what extent education is a force for good in changing people’s behaviors, but maybe some of us have been a little too quick to dismiss it entirely.

Sparkman: It kind of depends on what we mean when we say education. We found a couple of things that we think are particularly influential, building off of prior research. There’s the appeal to eat less meat versus eat no meat at all. In some of the research leading up to this study, it’s been shown that when people consider meat consumption in categorical terms, ‘don’t eat meat’ tends to turn people off from being willing to even entertain the idea of eating less. But if they think about meat on a continuum—so, how many of your 21 meals per week will have meat—people are a little more open to the idea of reduction.

Another thing we take advantage of in these appeals is that we leverage a variety of benefits, co-benefits for the environment, animal welfare and health. We also present all of these things as ‘this is direction that society is moving’. That’s been shown in prior research to be effective because when you talk about changes in norms over time, it can lead people to consider why other people are changing. And as they try to explain societal changes, they often end up generating arguments for why those things might be good ideas for themselves. It leads them to self-persuade.

We often think of conformity as peer pressure, but it’s actually a lot of informational influence. There’s a reason that people are doing what they’re doing, and as we try to understand that reasoning, we end up considering the advantages of doing so for ourselves as well.

Splitter: Why do you think the Reducetarian message had a longer lasting impact in the study?

Sparkman: There’s a couple reasons. It doesn’t ask people to completely limit consumption. Like I said, just thinking about meat consumption categorically turns people off from being willing to consider eating less, so we think that “reduce” itself is just an easier way to start things off. By elucidating this full argument in the form of an op-ed, you’re also essentially building associations for people with all of these potentially pertinent goals. They might be thinking about health over time. They might be thinking about environmental impacts or animal impacts over time. And as they do so, they’re going to start making connections between those kinds of goals and dietary choices around meat. We think that the reduce message did a good job of having those impacts start to become internalized for people. They saw the message and they sympathized with it, and that became part of the narrative for themselves, which they then carried forward in their decision-making over time.

Splitter: In the Reducetarian movement, how do you balance the need to be realistic about where people are with their meat-eating and the need for urgency and activism? I struggle with this myself— part of me wants to write about what terrible shape we’re in but then I also want to be realistic about what we all can do. I’m far from a vegan, so I’m arguing with myself too. Does this even make sense?

Kateman: It does makes sense, a therapist is good in this case. The reason this study came to be is that, in 2014, when I came up with this Reducetarian concept, I was with a colleague and I said I don’t know if what I'm doing has any impact. I was feeling kind of vulnerable, and I was seeing a lot of people around me feel very confident in what they were doing. That made me feel very isolated. But I started to learn there were people in our movement and in the world who were humble enough to acknowledge that we often do the best we can and we don’t always know what our impacts really are. So I wanted to do a study like this because I really wasn’t sure if the vegetarian message was going to work more than the ‘eat less meat’ message.

But yes, I often feel the sense of urgency that you’re describing. With my parents—family brings that out—my dad cares about his health but how do you convince someone you love that you want them to be on this planet for as long as possible and, hey, you never eat fruits and vegetables.

I try to enter this question of urgency from a sense of pragmatism. I try not to get emotional because I know from, not only now at 31, but from when I was in my teens and 20s, that telling my parents that they were evil or that they didn’t care about the world or all of these things that we might feel—it just doesn’t seem to work as well as what I think has been substantiated to some degree in this study.

Meeting people where they are works better than presenting them with a categorical imperative like don’t eat meat. That doesn’t mean I don’t sometimes feel angry or feel that sense of urgency but, at the end of the day, the planet, the animals, people’s health—they don’t care about my emotions. All that matters is the outcomes and the results. It seems to me that what works is making it as easy as possible for people to make choices that are in their interest and in the planet’s, and doing so as compassionately as possible.

I also find it very helpful to acknowledge all the ways that I’m an imperfect human being. I just ordered something on Amazon. I could probably donate more money or I could have been nicer to my mom. When was the last time I spoke to her on the phone? I mean, there’s just so many examples of me being a shitty person, that it feels pretty hypocritical for me to be pointing the finger at people. That tends to ground me and humble me.

Sparkman: I think that you’re right Jenny to point out this tension between do we do what we think people are already going to be pretty warmed up to do or do we aim for a new framework that implies bigger changes or that perhaps can deliver more justice? This is an issue that a variety of social movements deal with, and you’ll see this kind of thing get called out a lot, where people who are maybe more moderate on some issue will say, oh you can’t do that because it’s not popular. I think that there’s a tension there and it’s difficult, but I also think there are different roles for different people to play in different parts of the movement.

Our study is just one slice of persuasion, and it’s not a movement strategy writ large, but you could imagine having different actors in a whole scenario where somebody else does something that sounds quite extreme to you and then someone else comes along with something not as extreme to you. Now, by contrast, that latter idea sounds better.

Scientists are looking at when you have this collage of actors doing things, what is going to be most persuasive and how. But if the question is, when I walk up to somebody and I want to say something to them to try to persuade them, where should I aim? This study suggests we should probably aim just a few steps ahead of where they are right now.

In the real world, it’s more complicated. When you have bigger questions of strategy, you might come up with more elaborate answers that are a little more nuanced. There’s something to be said for having somebody just shift you over to the window so that you see the whole continuum of the movement. Then this solution actually seems like it’s a reasonable middle ground.

Splitter: What research gaps remain?

Sparkman: There’s definitely a couple. One is that in our first study we used a convenient sample—the people who were on this online platform—but those people tended to be younger and more liberal and more educated, and we got really great effects. In the second study, we used a national sample, and we find that we still get effects, but just with that sub-population that resembled the first population. We don’t really see it over the whole natural population. But from a practitioner standpoint, that’s actually not that big of a deal because, if you want to write an op-ed, that just means go to an outlet that has younger, more liberal and more educated folks, right? There’s plenty of outlets like that. Slate would be a great example.

The obvious next question is, okay, let’s say we want to get beyond that population segment to everybody else? What does that look like? I think we need more research to answer that question. We’d have to refine our question from how do we get some people to change to how do we get this or that very specific group of people to change? Conservatives, for example. Some of the work I've seen suggests that to the extent that you can find leadership in those populations and get them to be part of the messenger group, you’re going to do better. Of course, that’s obviously more difficult to put into practice. But these are all options that we can empirically test and see how effective those could be. Brian, do you have other thoughts on things you would like love to see researchers study?

Kateman: I mean, so many things, like testing the impacts of different media, documentaries, for example. I have my own film coming out in a couple months, but any kind of medium or vehicle for delivering the message could theoretically have different results. You can donate money. You can engage in politics. Ironically, sometimes we fixate a lot on our own personal choices, but there are many ways to participate.

I often wonder how we can get people motivated to do things outside their own personal choices and, lately, I’ve just been thinking so much about plant-based meat, cell-cultured meat and regenerative agriculture. I see those as essential ways to move away from factory farming, and I’m very excited about ways of engagement that would increase the chances that those would be adopted faster and more robustly across across populations. Plant-based meats are only something like 1.4 percent of the market. Cell-cultured meats aren’t even on the market here and regenerative agriculture is probably even less than plant-based. So there’s a lot of work to do and a lot of uncertainty. Gregg is going to be employed for a long time, I suspect.

Sparkman: There’s no shortage of things we don’t know.

Splitter: I’m not exactly sure how to phrase this next question but I feel conflicted sometimes about all of this brilliant strategy. It’s not even necessarily about Reducetarianism. Take Effective Altruism. On the one hand, here’s this highly logical and evidence-based approach, which absolutely appeals to a certain part of my brain, but on the other hand, there’s a part of me that feels like, goddamn it, you’re just so strategic and optimistic. Where’s the news for the people who just want to burn the world down and protest in the streets? I mean, not me, I’m not an activist, but as a Gen X-er, doom and gloom is my jam. It resonates with me far more than optimism. I don't know, I guess I probably do need a therapist. You probably hit the nail on the head with that one, but this is really something that constantly bothers me.

Kateman: I think about this too. I’m sure Greg will have a different interpretation of this but, yeah, I do worry about sort of watering down the message, or even something called moral licensing (basically when you sort of do one thing that’s good and then you kind of ignore all the other things that still need to be done). Somebody participates in Meatless Monday and then they feel like they’ve done enough, for example. I think there’s a balance between celebrating the successes and providing people with the honest-to-God truth that there are billions of animals being tortured on factory farms and if we don’t make major changes to our diet, we’re gonna be in trouble.

I think that’s the role that other activists play. I like what Greg said about the collage of actors. There’s a role for folks to play. I don’t know what their exact role is, but I think there is a role for folks who want to push and challenge and I think there is also a role for folks like me to tell people they’re doing a great job for participating in Meatless Monday.

The thing that strikes me is that the average person is eating 220 pounds of meat each year. If someone tells me that they cut back ten percent, it strikes me as odd to focus my energy on that person when there are so many other people doing absolutely nothing at all. In my experience, when I tell people that they should go vegan, for me that just equates to giving up all the foods that you love, having awkward interactions with your family at Thanksgiving and holidays, being highly offensive and alienating yourself socially. That’s just my reaction to when people used to tell me that.

I understand your fears about watering down and excusing people’s behavior though. That’s why I was surprised that this study worked because I was under the impression that none of this stuff works—telling people to eat less meat doesn’t work, telling people to go vegan doesn’t work, telling people anything doesn’t work—that our power to change people’s attitudes and behavior is limited, and that’s why we need to use capitalism. That’s why we need to use market forces. That’s definitely the narrative that has infiltrated even my own brain over the past several years, so I was very excited to see a sliver of hope towards actually changing people’s behaviors.

Splitter: For me, part of it is seeing so many plant based executives kind of take over the messaging with what seems like this very corporate, positive spin. Like, don’t use the word “vegan” in your article, that kind of thing. I just want to say, calm down with the marketing, there is a reality here that I want to cover.

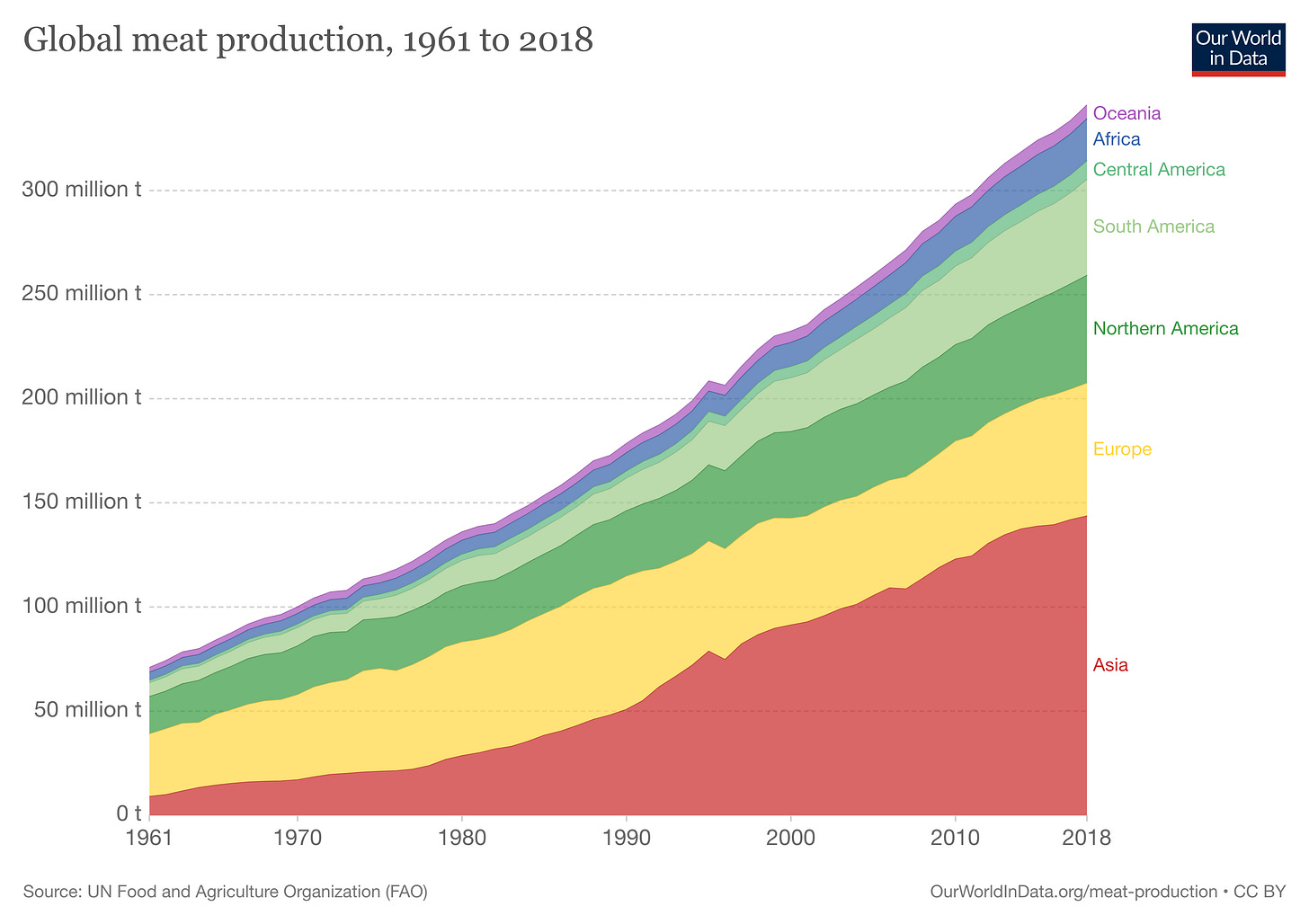

Kateman: I know what you mean about this advocacy versus truth thing. We still need to engage in truth, right? Take the fact that meat consumption is going up. So if it’s bad to tell people that meat consumption is going up because we know that people are more likely to want to imitate the behaviors of others, as an activist, should I lie to people and say that meat consumption is falling left and right? Like my colleagues sometimes get mad at me when I share an article that says meat consumption is on the rise because it’s inconvenient to the message.

Sparkman: Yeah, there are a few different questions I’m hearing. Are we appealing to the lowest common denominator? Are we really being too anodyne? Are we not rocking the boat enough in order to be persuasive? Are we being too incrementalist? These are all super important questions. One way to think about our study is giving you a foot in the door. It doesn't mean that we should stop there. You can build off of that.

There’s also the problem of what some people call a single action bias, where you do just one thing and it alleviates the negative effect that motivated you to do something in the first place, and then you don’t do anything else. Some of the work I've done that’s in a similar-ish domain is on how people’s environmental behavior corresponds to their environmental policy attitudes. Does your behavioral change make you feel that we don’t now need policy change, because that may make your utilities go up, for example?

Here’s how you can manage that issue, especially from a research standpoint. When people do take action, you want to frame their action as something that reflects both their identity and their values. When they do that, they’re far more likely to take consistent types of actions in the future and become even stronger supporters of the movement. So if you frame behavioral change in terms of great progress, people might want to simply rest on their laurels. But if you emphasize their commitment over the quantitative progress, then their behavior becomes internalized, which deepens their values and their incentive to act on those values in the future.

Splitter: Sounds like parenting advice…(praise effort not achievement)

Sparkman: There is also research on the tendency for people to internalize their reasons for action. When people take action and you ask them later why they did it, they will tend to point to internal reasons. That’s because we don’t like to admit that we did something because of an external influence. So if someone reduces their meat consumption, they would be more likely to say it’s because they care about the environment or animal welfare, for example. But you can also pair interventions with something that locks it down. So you have this foot in the door, and then what do you do to leverage that to get consistent action in the future? You can ask, do you want to support this animal welfare policy? Does that make sense given the actions you’ve already taken? So you stack these effects going forward. That could be one way to build up to the bigger kinds of change we want to see.

You might first focus on getting people to drift over to your side of the debate, but then once they’re here, you break down for them just how crazy this space actually is, get into the more doom and gloom that you’re talking about. But you don’t walk into a party and just start yelling at people, right? You warm people up first, and then you introduce the more intense stuff. That would be my intuition of how you avoid these incremental concerns but still take to heart the fact that asking people to immediately make radical changes isn’t always going to be the best approach.

I also want to flag that we’ve been talking about incremental changes in personal behavior but I don’t actually have that same prescriptive advice in the policy sphere. That’s because I’m not super persuaded that what politicians think is normal is actually normal. I want them to make the changes that are right, even if those seem drastic. I’m an anti-incrementalist in the policy space.

Norms are also chronically misperceived in the policy space. What people think is normal is often skewed about twenty years behind and to the right. For example, people don’t understand how popular Medicare For All actually is. They don’t understand how popular raising the minimum wage is, that the vast majority favors it. When people try to do the more incremental thing in the policy sphere, what they’re actually doing is the contemporarily conservative thing. We call that pluralistic ignorance, by the way, where there’s a shared misrepresentation of a norm, that everybody thinks they know what everybody else thinks. And people are all wrong in the same direction.

From a policy standpoint in the animal welfare space, people might be surprised to learn where the public attitude is on things, because nobody likes animal suffering. Most say, no, I’d prefer it not to happen. But that doesn’t get translated into policy very quickly in that space at all. There’s a disconnect. Even in our study, the thing that might seem incremental or just a few steps ahead of where people are in terms of behavior would actually be dramatically changing things from a policy standpoint, and that’s because the policy is so far behind where people actually are.

What I’m reading

Coming soon: my New Books Network interview with Beloved Beasts author Michelle Nijhuis. The book is a fascinating and surprising history of the conservation movement. Give it a read.

What I’m cooking

https://cooking.nytimes.com/recipes/1021508-creamy-vegan-tofu-noodles