4 arguments about meat, explained

Four defenses for ‘business-as-usual’ meat-eating, described and debunked.

Debates can feed our curiosity. I’ve never played Wordle, for example, but I started writing about food systems emissions after falling down a rabbit hole of Twitter debates about meat. But debates by their very nature tend to put two sides forward as if they’re both on equal footing, and it can be hard to figure out which set of facts are correct.

With that in mind, here are four arguments for eating beef as usual that tend to come up in debates about meat, broken down and explained with facts and context. Some of these can get complicated, so I’m mostly hitting the high notes with links to further reading if you’re curious.

Four Defenses for ‘Business-As-Usual’ Meat-Eating, Explained

The claim: it’s the planes and the cars, not the cows. Fossil fuels are the real climate problem, the argument goes, so don’t worry about emissions from beef.

Context: Because food system emissions in the US are 10 percent of the total pie while transportation emissions make up a more sizable 29 percent, some people argue that the US food system isn’t contributing to global climate change, especially since the US has a far more efficient farming sector than many other parts of the world. But that 10 percent is a somewhat misleading number. In the US, energy emissions are also much higher than in some other parts of the world. By comparison, agriculture’s share looks smaller.

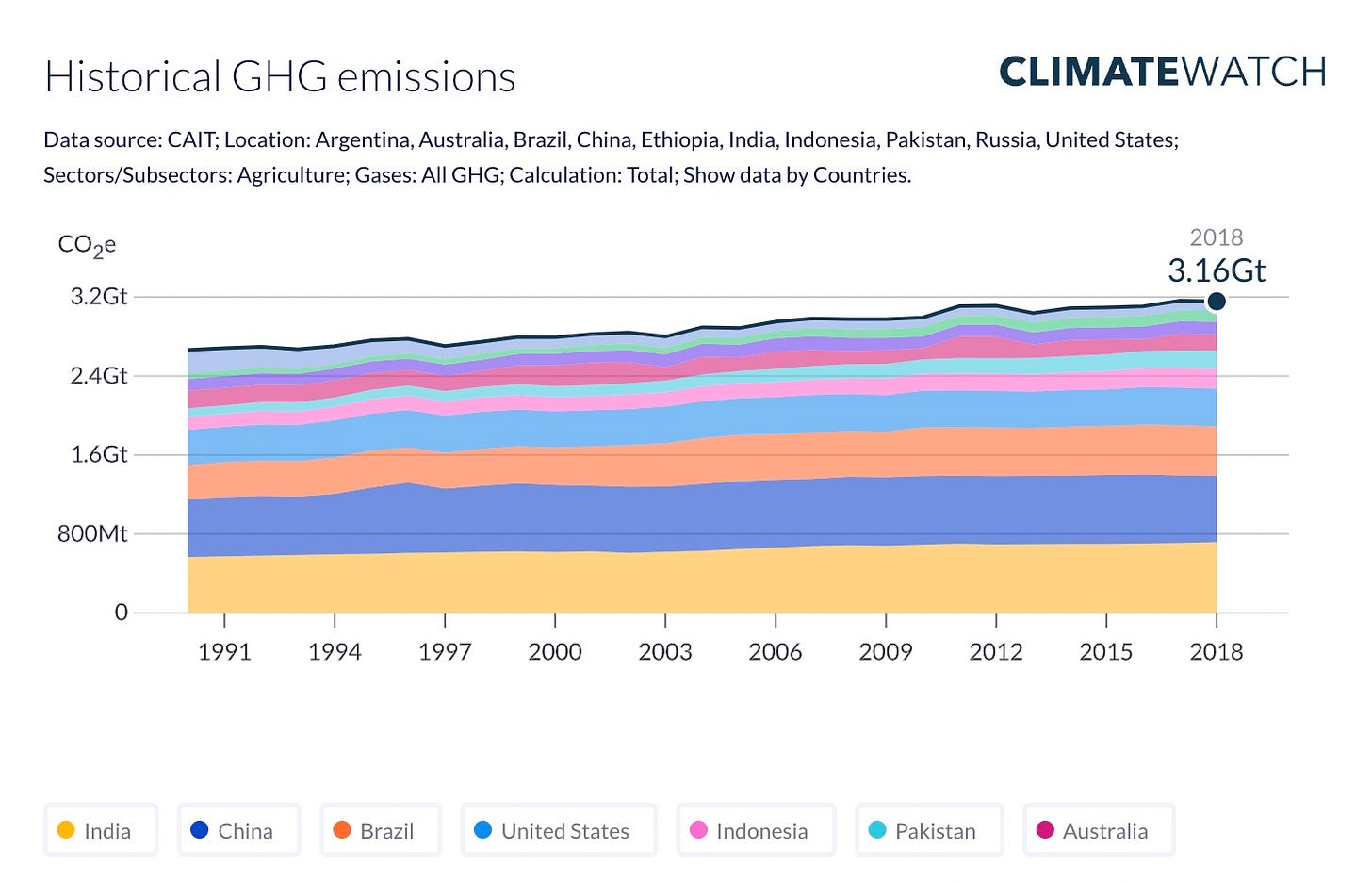

When we look at food systems emissions on a per capita basis, we see that the US is the fourth largest emitter, increasing by 12 percent between 1990 and 2019, according to the EPA. Given the urgent need for climate action expressed in the latest IPCC report, we need to be addressing every sector right now, and that includes food system emissions.

Further reading: Can You Trust a Pro-Beef Professor? It’s Complicated. Undark

The claim: it’s not the cow, it’s the how. Sure, factory farmed beef is bad for the planet, according to this argument, but meat raised regeneratively is carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative.

Context: Many regenerative livestock farms use a grazing method called “mob grazing,” where cattle are moved from area to area to graze the grass and trample the ground, which does indeed cause a short-term increase in soil carbon at the upper levels of the soil. But that carbon doesn’t tend to stick around permanently, which is a problem if you’re relying on it to offset the emissions of the steak you raised.

There isn’t consensus on how to get carbon in agricultural soils to stay put, or even whether it’s possible to do so in the first place. This is just one of the many fascinating and evolving areas of soil science research. Ultimately, the uncertainty around carbon sequestration means we can’t rely on these claims as an offset for what are very certain and long-lasting emissions. Claims of net-zero or carbon-negative beef just don’t hold up.

A Guide to High Quality Carbon Offsets

Another problem is that meat raised regeneratively requires a lot more land, more than twice the amount of land in the case of “carbon-negative” meat from White Oak Pastures. Land has a climate cost. It’s not a free resource, which is something we need to be thinking about more in food systems and climate change discussions (more on that below).

The US eats four times the amount of beef as the rest of the world, and raising all of that meat regeneratively would mean a huge increase in our land use needs, which would either lead to more deforestation or converting a lot of cropland to grazing land to add more cattle and other livestock, which would also increase methane and nitrous oxide emissions, or all of the above. The bottom line: we can’t lower our carbon footprint by swapping regenerative beef for factory-farmed beef.

Some researchers and regenerative advocates suggest the US could increase regenerative operations without increasing land use if we greatly reduce meat consumption and convert some farmland used now for corn that mostly goes to ethanol. Meat would become an occasional indulgence, purchased only from smaller-scale regenerative operations. It’s also important to note that regenerative practices like conservation tillage and cover crops are excellent for soil health, reducing soil erosion and waterway pollution.

But back to the land problem — this would likely mean reducing beef even more than is already recommended by climate action groups, which we already aren’t doing anyway. But as I’ve said before elsewhere, I’m not saying big changes to our food system aren’t needed and possible. We just have to talk honestly and specifically about what the path to get there would look like, including the difficult challenges. When I covered what a possible plant-based transition might look like for Vox, for example, my reporting detailed the ways in which this transition is still very speculative and complicated.

Further reading: Spencer Roberts’s latest piece in Jacobin critiques the methods used in the White Oaks Farm study and reports on the ways in which some regenerative farmers are partnering with large corporate interests rather than dismantling them. How Big Ag Bankrolled Regenerative Ranching, Spencer Roberts, Jacobin.

The claim: we don’t need to worry about methane like we worry about carbon emissions because methane is a short-lived pollutant. It only hangs around in the atmosphere for about a decade, unlike carbon that lasts for 100 years.

Context: Methane is shorter lived in the atmosphere, but it’s also a far more potent pollutant than carbon, so it causes more damage while it’s here. Meanwhile, methane emissions are increasing everywhere, so we need to worry about both the carbon and the methane, not to mention the nitrous oxide emissions and other types of air and water pollution caused by animal farming.

Further reading: Why Methane Is a Large and Underestimated Threat to Climate Goals - Yale E360

The claim: we can make beef and dairy “climate-neutral” by limiting the number of cows. Just keep herds at a constant rate and you won’t get added pollution.

Context: Unless every region agrees to that limit, farms will just expand somewhere else to meet growing beef and dairy demand. And demand is growing, mostly because two things are happening simultaneously: we aren’t reducing our consumption and the world’s population continues to grow.

“Climate-neutral,” much like net-zero, is a meaningless target when it’s used by polluting industries to persuade the public that they’re reducing emissions. These targets only have meaning when there is a plan for how to get there, including substantive milestones that hold up to scientific scrutiny.

Further reading: Beef Industry Tries to Erase Its Emissions with Fuzzy Methane Math, Bloomberg Green

The claim: there’s no deforestation in the US, so just eat US beef. Forests are growing in the US, so only beef raised in places like Brazil are causing deforestation.

Context: Climate change is a global problem, and agriculture is a globally-traded industry. It’s impossible to cut our food system off from the rest of the world and behave like what we eat doesn’t impact global commodity crops in other places. The trade wars with China and the current war in the Ukraine illustrate this very point.

One little-understood area of food systems research is the role land plays in climate change calculations. In the US, most of our deforestation happened centuries ago. But historical deforestation can have a climate change impact felt today. Using land to grow food provides calories and jobs and other benefits, of course, but it also comes at a climate cost, one we need to factor into emissions calculations.

Whenever land is converted from wild ecosystem to farmland, whether today in the Cerrado in Brazil or in the past in the US, there is a “carbon opportunity cost,” a lost opportunity to store carbon in the ground and out of the atmosphere. Researchers say that cost should be factored into greenhouse gas emissions accounting, in addition to methane emissions and other sources of pollution, to give us a more accurate picture of the cost of our dietary choices. Ultimately, because beef has an especially high land cost as well as methane cost, we need to eat much less of it in order to help curb climate emissions.

Further reading: How to make agriculture carbon-neutral, Tim Searchinger, World Resources Institute; What are the carbon opportunity costs of our food?, Hannah Ritchie, Our World in Data

Got questions or thoughts about any of these? Share this post and tag me on Twitter @jennysplitter.

Hits and Misses: What I cooked for my non-vegan family this week

Hits: Seems weird to be making pesto pasta in March but I had some fresh basil that was about to turn and the weather was warm. Maybe I’ll start calling it “climate adaptation pesto,” she writes gloomily. I also sprinkled a bit of a new-to-me nutritional yeast on top. I’ve not always been a fan of the “nooch,” but after putting out a call for recommendations on Twitter, I ended up trying a new brand, Anthony’s (thank you, @veganroundtable!). It’s great, actually. My younger kid says it tastes just like parmesan, so that’s a win. Also, these vegan tahini noodles from Portland food blogger Alexandra Jones were a big hit.

Misses: We did more takeout than usual over the past two weeks, which is not my ideal. But I’m lucky there are lots of great takeout options in DC that are either fully vegan or have great vegan options, including pizza from &pizza and HipCityVeg. While I usually have to avoid the nut-based cheeses due to my younger kid’s food allergy, I was even able to finally try Vertage’s cheese in quesadillas at Cielo Rojo last week. That stuff is freaking delicious.

Now listening

A couple of weeks ago (I think, time has no meaning), I was thrilled to speak with Ana Bradley, Executive Director of Sentient Media, on the Sentient Media podcast. We talked about animal farming, vegans on Twitter, our takes on the NYT op-ed, the importance of staying curious and lots of other things! Give it a listen:

I'm a new subscriber who found your newsletter via twitter (& admittedly, longtime vegan) who appreciates your sense - and connectivity of topics - so, so much.